The basic Service Based Development Process I described previously described an end-to-end delivery process for creating services, whether these be cloud-based services or traditional ones running on a an enterprise service bus. The process consisted of a number of activities (where an activity groups together several tasks) as follows:

- Business Modelling – Develop business process models to understand the business activities that need to take place. Probably a mix of as-is and to-be as well as manual and automated activities.

- Solution Architecture and Design – Create the architecture for the solution, decides what services are to be used, what platform and delivery environment (public/private cloud, ESB etc) will be used.

- Solution Assembly/Implementation – Assemble the services into an application and implement using the appropriate technology. Hopefully much of this will be done using tools that generate the appropriate process flows and pull in the right services.

- Service Identification – Decide what new services need to be specified (i.e. not already in the Service Portfolio).

- Service Specification – Specify services, their contracts (functional and service levels).

- Existing Asset Analysis – What assets does the enterprise already have that could be service enabled (legacy code that could be wrappered etc).

- Service Realisation – Decide what technology will be used to implement services.

- Service Implementation – Implement services using the chosen technology.

- Service Platform Design and Installation – Having decided the service runtime environment design and install it. For cloud-based services this means procuring the right cloud resources.

- Service Operations and Management – Manage and run the service.

- Service Portfolio Management – Ensure the Service Portfolio kept up to date.

In the example process we have seen so far each of these activities is composed together in such a way that a complete solution can be built out of a set of services that are deployed into a run-time environment. But that is not the only way these activities can be composed. A better way is to compose activities into capability patterns. Capability patterns are comprised of tasks and/or activities that can be composed into ‘higher-order’ capability patterns or delivery processes. They are reusable patterns which can applied across a range of delivery processes. Capability patterns have input/output work products which together define the ‘contractual boundary’ to which performers of the capability pattern must conform (more on this next time).

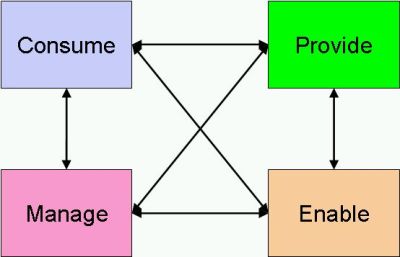

The delivery process described in part 1 is actually comprised of four capability patterns, each of which could be a process in its own right, or composed into different delivery processes. The four capability patterns are:

- Provide Capability: Create a new or updated business process/capability based on user requirements. Uses existing services or specifies new ones where needed. Uses tasks mainly from the Consume discipline group.

- Provide Service: Specify, design and build a new service according to business need. Certify, publish and deploy the service into the operational environment. Uses tasks mainly from the Provide discipline group.

- Manage Service Portfolio: Create and maintain a service portfolio with an initial set of specified services. Ensure services are certified. Uses tasks from the Manage group.

- Provide Environment: Design, build, test, install and run a new environment capable of running services. Uses tasks mainly from the Enable group.

Using the same diagrams as before here are the above four capability patterns laid out in terms of disciplines and phases from OpenUP.

|

| Provide Capability |

|

| Provide Service |

|

| Manage Service Portfolio |

|

| Provide Environment |

In the third part I’ll look at the work products which together define the ‘contractual boundary’ to which performers of each of the capability patterns must conform.

The ideas in this blog were jointly developed with my ex-IBM colleague Bruce Anderson.