John Templeton, the American-born British stock investor, once said: “The four most expensive words in the English language are, ‘This time it’s different.’”

Templeton was referring to people and institutions who had invested in the next ‘big thing’ believing that this time it was different, the bubble could not possibly burst and their investments were sure to be safe. But then, for whatever reason, the bubble did burst and fortunes were lost.

Take as an example the tech boom of the late 1980s and 1990s. Previously unimagined technologies that no one could ever see any sign of failing meant investors poured their money into this boom. Then it all collapsed and many fortunes were lost as the Nasdaq dropped 75 percent.

It seems to be an immutable law of economics that busts will follow booms as sure as night follows day. The trick then is to predict the boom and exit your investment at the right time – not too soon and not too late, to paraphrase Goldilocks.

Most recently the phrase “this time it’s different” is being applied to the wave of AI technology which has been hitting our shores, especially since the widespread release of large language model technologies which current AI tools like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s PaLM, and Meta’s LLaMA use as their underpinning.

Which brings me to the book The Coming Wave by Mustafa Suleyman.

Suleyman was the co-founder of DeepMind (now owned by Google) and is currently CEO of Inflection an AI ‘studio’ that, according to its company blurb is “creating a personal AI for everyone”.

The Coming Wave provides us with an overview not just of the capabilities of current AI systems but also contains a warning which Suleyman refers to as the containment problem. If our future is to depend on AI technology (which it increasingly looks like it will given that, according to Suleyman, LLMs are the “fastest, diffusing consumer models we have ever seen“) how do you make it a force for good rather than evil whereby a bunch of ‘bad actors’ could imperil our very existence? In other words, how do you monitor, control and limit (or even prevent) this technology?

Suleyman’s central premise in this book is that the coming technological wave of AI is different from any that have gone before for five reasons which makes containment very difficult (if not impossible). In summary, these are:

- Reason #1: Asymmetry – the potential imbalances or disparities caused by artificial intelligence systems being able to transfer extreme power from state to individual actors.

- Reason #2: Exponentiality – the phenomenon where the capabilities of AI systems, such as processing power, data storage, or problem-solving ability, increase at an accelerating pace over time. This rapid growth is often driven by breakthroughs in algorithms, hardware, and the availability of large datasets.

- Reason #3: Generality – the ability of an artificial intelligence system to apply their knowledge, skills, or capabilities across a wide range of tasks or domains.

- Reason #4: Autonomy – the ability of an artificial intelligence system or agent to operate and make decisions independently, without direct human intervention.

- Reason #5: Technological Hegemony – the malignant concentrations of power that inhibit innovation in the public interest, distort our information systems, and threaten our national security.

Suleyman’s book goes into each of these attributes in detail and I do not intend to repeat any of that here (buy the book or watch his explainer video). Suffice it to say however that collectively these attributes mean that this technology is about to deliver us nothing less than a radical proliferation of power which, if unchecked, could lead to one of two possible (and equally undesirable) outcomes:.

- A surveillance state (which China is currently building and exporting).

- An eventual catastrophe born of runaway development.

Other technologies have had one or maybe two of these capabilities but I don’t believe any have had all five, certainly at the level AI has. For example electricity was a general purpose technology with multiple applications but even now individuals cannot build their own generators (easily) and there is certainly not any autonomy in power generation. The internet comes closest to having all five attributes but it is not currently autonomous (though AI itself threatens to change that).

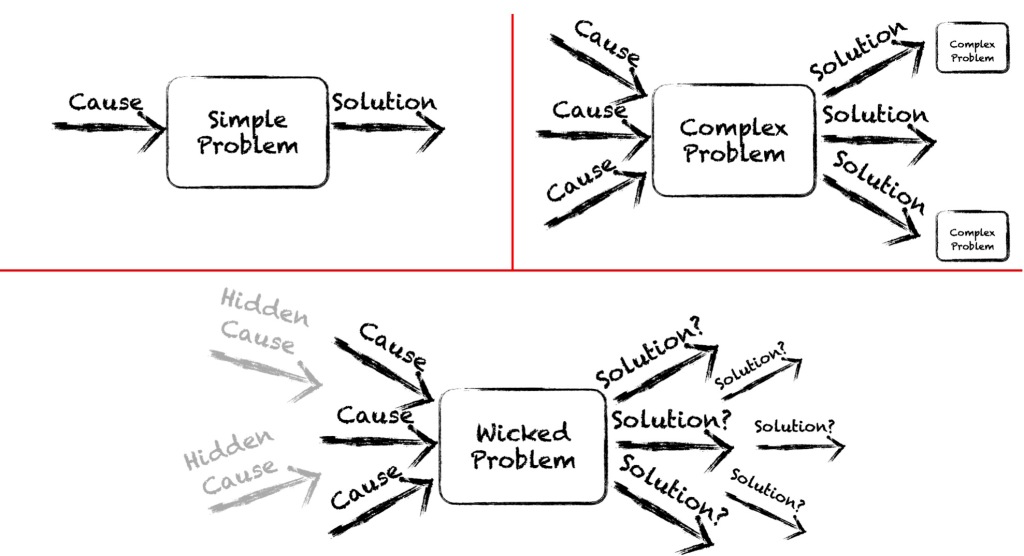

To be fair, Suleyman does not just present us with what, by any measure, is a truly wicked problem he also offers a ten point plan for for how we might begin to address the containment problem and at least dilute the effects the coming wave might have. These stretch from including built in safety measures to prevent AI from acting autonomously in an uncontrolled fashion through regulation by governments right up to cultivating a culture around this technology that treats it with caution from the outset rather than adopting the move fast and break things philosophy of Mark Zuckerberg. Again, get the book to find out more about what these measures might involve.

My more immediate concerns are not based solely on the five features described in The Coming Wave but on a sixth feature I have observed which I believe is equally important and increasingly overlooked by our rush to embrace AI. This is:

- Reason #6: Techno-paralysis – the state of being overwhelmed or paralysed by the rapid pace of technological change caused by technology systems.

As is the case of the impact of the five features of Suleyman’s coming wave I see two, equally undesirable outcomes of techno-paralysis:

- People become so overwhelmed and fearful because of their lack of understanding of these technological changes they choose to withdraw from their use entirely. Maybe not just “dropping out” in an attempt to return to what they see as a better world, one where they had more control, but by violently protesting and attacking the people and the organisations they see as being responsible for this “progress”. I’m talking the Tolpuddle Martyrs here but on a scale that can be achieved using the organisational capabilities of our hyper-connected world.

- Rather than fighting against techno-paralysis we become irretrevably sucked into the systems that are creating and propagating these new technologies and, to coin a phrase, “drink the Kool-Aid”. The former Greek finance minister and maverick economist Yanis Varoufakis, refers to these systems, and the companies behind them, as the technofeudalists. We have become subservient to these tech overlords (i.e. Amazon, Alphabet, Apple, Meta and Microsoft) by handing over our data to their cloud spaces. By spending all of our time scrolling and browsing digital media we are acting as ‘cloud-serfs’ — working as unpaid producers of data to disproportionately benefit these digital overlords.

There is a reason why the big-five tech overlords are spending hundreds of billions of dollars between them on AI research, LLM training and acquisitions. For each of them this is the next beachhead that must be conquered and occupied, the spoils of which will be huge for those who get their first. Not just in terms of potential revenue but also in terms of new cloud-serfs captured. We run the risk of AI being the new tool of choice in weaponising the cloud to capture larger portions of our time in servitude to these companies who produce evermore ingenious ways of controlling our thoughts, actions and minds.

So how might we deal with this potentially undesirable outcome of the coming wave of AI? Surely it has to be through education? Not just of our children but of everyone who has a vested interest in a future where we control our AI and not the other way round.

Last November the UK governments Department for Education (DfE) released the results from a Call for Evidence on the use of GenAI in education. The report highlighted the following benefits:

- Freeing up teacher time (e.g. on administrative tasks) to focus on better student interaction.

- Improving teaching and education materials to aid creativity by suggesting new ideas and approaches to teaching.

- Helping with assessment and marking.

- Adaptive teaching by analysing students’ performance and pace, and to tailor educational materials accordingly.

- Better accessibility and inclusion e.g. for SEND students, teaching materials could be more easily and quickly differentiated for their specific.

whilst also highlighting some potential risks including:

- An over reliance on AI tools (by students and staff) which would compromise their knowledge and skill development by encouraging them to passively consume information.

- Tendency of GenAI tools to produce inaccurate, biased and harmful outputs.

- Potential for plagiarism and damage to academic integrity.

- Danger that AI will be used for the replacement or undermining of teachers.

- Exacerbation of digital divides and problems of teaching AI literacy in such a fast changing field.

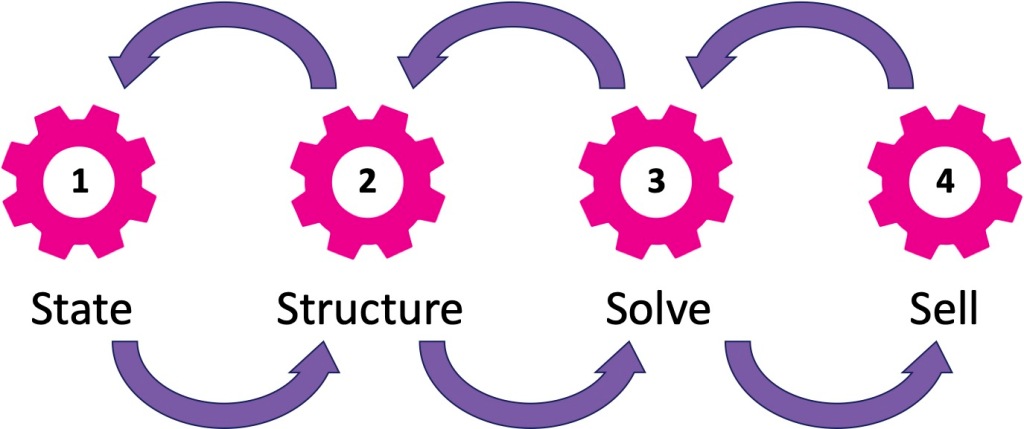

I believe that to address these concerns effectively, legislators should consider implementing the following seven point plan:

- Regulatory Framework: Establish a regulatory framework that outlines the ethical and responsible use of AI in education. This framework should address issues such as data privacy, algorithm transparency, and accountability for AI systems deployed in educational settings.

- Teacher Training and Support: Provide professional development opportunities and resources for educators to effectively integrate AI tools into their teaching practices. Emphasize the importance of maintaining a balance between AI-assisted instruction and traditional teaching methods to ensure active student engagement and critical thinking.

- Quality Assurance: Implement mechanisms for evaluating the accuracy, bias, and reliability of AI-generated content and assessments. Encourage the use of diverse datasets and algorithms to mitigate the risk of producing biased or harmful outputs.

- Promotion of AI Literacy: Integrate AI literacy education into the curriculum to equip students with the knowledge and skills needed to understand, evaluate, and interact with AI technologies responsibly. Foster a culture of critical thinking and digital citizenship to empower students to navigate the complexities of the digital world.

- Collaboration with Industry and Research: Foster collaboration between policymakers, educators, researchers, and industry stakeholders to promote innovation and address emerging challenges in AI education. Support initiatives that facilitate knowledge sharing, research partnerships, and technology development to advance the field of AI in education.

- Inclusive Access: Ensure equitable access to AI technologies and resources for all students, regardless of their gender, socioeconomic background or learning abilities. Invest in infrastructure and initiatives to bridge the digital divide and provide support for students with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) to benefit from AI-enabled educational tools.

- Continuous Monitoring and Evaluation: Regularly monitor and evaluate the implementation of AI in education to identify potential risks, challenges, and opportunities for improvement. Collect feedback from stakeholders, including students, teachers, parents, and educational institutions, to inform evidence-based policymaking and decision-making processes.

The coming AI wave cannot be another technology that we let wash over and envelop us. Indeed Suleyman himself towards the end of his book makes the following observations…

“Technologist cannot be distant, disconnected architects of the future, listening only to themselves.“

Technologists must also be credible critics who…

“…must be practitioners. Building the right technology, having the practical means to change its course, not just observing and commenting, but actively showing the way, making the change, effecting the necessary actions at source, means critics need to be involved.“

If we are to avoid widespread techno-paralysis caused by this coming wave than we need a 21st century education system that is capable of creating digital citizens that can live and work in this brave new world.